Ripple Effects of Microplastics in Canadian Lakes

Ripple Effects Of Microplastics In Canadian Lakes

Ecosystems are incredibly interconnected. The indirect (ripple) effects of microplastic impacts on ecosystems have been a missing link in research, but not for long.

Dr. Michael Rennie, Canadian Research Chair at Lakehead University, is a key member of a research group studying the effects of microplastics on ecosystems.

Dr. Rennie is a member of Dr. Chelsea Rochman‘s team, including government agencies like Environment and Climate Change Canada and Ontario’s Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks.

Moving beyond individual impacts, Dr. Rennie spikes entire ecosystems with microplastics to see what could happen to our Canadian lakes at different levels of microplastic contamination.

"...[Indirect] impacts have the greatest relevance for how we manage microplastics in our ecosystem,” Dr. Rennie.

“I look forward to this experiment because you cannot always predict these indirect effects, and you certainly cannot evaluate them in a lab setting, but they are often the most interesting. These impacts have the greatest relevance for how we manage microplastics in our ecosystem,” explains Dr. Rennie.

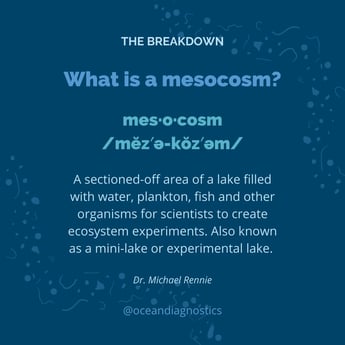

The team of researchers creates a “mesocosm” lake at the IISD Experimental Lake Area (ELA) in Ontario. The ELA is a world-renowned location in Ontario where researchers can conduct ecosystem-level experiments in the environment in real-time.

The mesocosm is essentially a “mini-lake within the lake” as Dr. Rennie puts it. It is a sectioned-off area of the lake filled with water, plankton, fish and more.

These mini lakes are as good a representation of aquatic communities as one can get before examining impacts at the whole lake level, which makes this experiment even more crucial.

The team will add certain levels of microplastics to these "mini-lakes" and observe the changes at different microplastic level gradients.

When asked what he is expecting to find, Dr. Rennie notes: “some of the most interesting findings are the ones we aren’t expecting, and often they come from indirect effects.”

For example, a few years ago, Dr. Rennie conducted an experiment where synthetic estrogen was added to an ELA lake. They found only fathead minnows were impacted by the synthetic estrogen itself, but there were several indirect effects: The lake trout that relied on the minnows for food started to decrease in numbers and the zooplankton that the minnows ate began to increase in numbers.

Mesocosm studies like this bridge the gap between research on how toxic microplastics are to what might happen in an entire ecosystem.

In Canada, lakes and rivers are all managed at an ecosystem or stock level, so it makes sense to understand the risk of microplastics to the ecosystem overall. It can help inform government decisions that may limit the amount of plastic released into the environment.

This is not the first time the group has spent time at the ELA looking for plastic. A couple of years ago, they conducted a baseline study to measure the number of plastics in the Ontario ELA lakes.

As expected, they found microplastics but, interestingly, the amount of microplastics did not vary when compared to other lakes with higher human activity.

Even the most remote lakes had similar levels of plastics in the ecosystems and, typically, these plastics were fibers.

This finding led the researchers to look at microfibers in the air. Microplastics – especially fibers - float in the air around us and can enter lakes and rivers.

This could explain why lakes with little human activity have similar amounts of microplastics. Dr. Rennie investigates this question and other questions as part of this large collaborative project.

His students work on several other questions that fall under the umbrella of this initiative, including how microplastics impact the rate at which fish intake oxygen and how chemical additives may alter what proteins are produced in juvenile lake trout.

Their goal is to complete a whole-lake edition of the microplastics study, where they will add microplastics to an entire ELA lake.

"...This whole lake experiment will help us understand what the fate and effects of microplastics are at the ecosystem level.” - Dr. Rennie.

Dr. Rennie says, “we know that plastics can be consumed, we know they can sometimes ‘translocate’ - move from the gut to the tissues - but there are still many questions. This whole lake experiment will help us understand what the fate and effects of microplastics are at the ecosystem level.”

These questions will help inform how concerned we should be about microplastic pollution in our freshwater systems.

"There is enough justification to say we should take some kind of action and any kind of additional information we discover … should only increase the urgency." - Dr. Rennie.

Dr. Rennie notes, “there is enough justification to say we should take some kind of action and any kind of additional information we discover … should only increase the urgency.”

The last thing we want to see when we are out enjoying nature in our own towns or on holiday is washed-up plastic debris. There is reason right now to try to minimize how much plastic gets into our environment.

For Dr. Rennie, his microplastic concern is rooted in the fact that we find it everywhere, even in the most obscure plastics like Arctic ice, and from a strictly aesthetic point of view, he’d prefer not to have plastics in the things he consumers. “It’s just an unpleasant thing to consider,” he says.

“A Ziplock bag in my house has a life of 3.5 years on average,” jokes Dr. Rennie.

There are decisions we can make as consumers to help cut down on plastics. Dr. Rennie suggests bringing your reusable bags to grocery stores, including reusable produce bags.

“A Ziplock bag in my house has a life of 3.5 years on average,” jokes Dr. Rennie. There are ways we can reduce plastics at home, which include washing traditionally single-use plastic products and reusing them.

Of course, other alternatives have environmental concerns as well, so be mindful of your consumption.

To make a big difference, we also need government to act. Dr. Rennie argues that good governments can play a more active role in making sure that companies are held responsible for taking products back at their end of life.

To make sure governments know you care about plastic management, write your MP. Our leaders won’t know what you care about unless you tell them. Dr. Rennie notes that almost every time you write your MP or MPP, you will get a response. It can truly make a difference.

We are eager to see the results of Dr. Rennie and the team of collaborators’ lake studies. We need more information on the impacts of microplastics at the ecosystem level, not only to inform solutions but for our own wellbeing.

Many of us have enjoyed freshwater lakes and streams while living in Canada. If microplastics impact different organisms in these lakes, the ripple effects are of utmost concern.

Stay tuned for the team’s results and keep working towards reducing plastic in your life!

Share our content under the hashtag #BeatPlasticPollution to spread the word.

We love our Canadian lakes, let’s keep them fresh and full of life.

Ocean Diagnostics Inc. is an environmental impact company that develops technologies and laboratory capabilities to standardize microplastics data collection and analysis. The company works closely with academic and government partners to advance microplastic science. ODI has partnered with Environment and Climate Change Canada to share information on microplastic pollution from Canadian plastic experts. Learn more here.

Follow #BeatPlasticPollution for the latest news.